UArizona Postdoc’s 50-Mile Run for Indigenous Scientists Featured in Patagonia Film

Native News Online (December 13, 2021) by Kyle Mittan

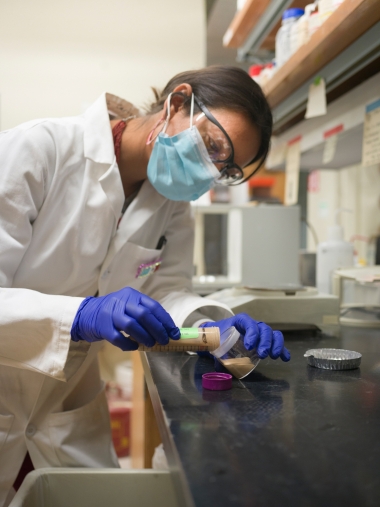

When Lydia Jennings finally finished her doctoral program in soil microbiology, a lockdown amid the COVID-19 pandemic made celebrating difficult.

But a national conversation on diversity and representation in many disciplines, including the sciences, presented an opportunity for Jennings, who had just earned her Ph.D. from the Department of Environmental Science in the University of Arizona College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

“In addition to celebrating, I wanted to create a resource for people to learn about many of the scholars who I personally have been mentored by or who I looked up to” said Jennings, who is now a postdoctoral research associate in UArizona’s Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health. “I didn’t know many Indigenous scientists until I started my Ph.D. program, and that’s a really big shame.”

Jennings, a member of the Huichol and Pascua Yaqui Indigenous communities, turned to one of her earliest passions – running – to highlight Indigenous scholars’ countless contributions. A 50-mile honor run, which she completed on March 20, 2021, was dedicated to Indigenous scientists past, present and future.

Jennings’ run and her research on soil health and Indigenous policy are the focus of a new documentary, “Run to be Visible,” produced and released by the outdoor clothing and gear company Patagonia.

Since the film premiered on YouTube on Oct. 20, it has been viewed online more than 530,000 times.

It’s also helped raise more than $9,000 for a scholarship fund at the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, a nonprofit organization aimed at increasing representation of Indigenous people in science, technology, engineering and math. The scholarships support Indigenous students facing challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A link at the end of the film takes viewers to a page on the Patagonia website where donations can be made to organizations such as the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, the Native American Fish and Wildlife Society, the Native American Agricultural Fund and more.

The film also has been screened at events in California and Colorado, which included panel discussions with some of the scientists Jennings honored. Students, especially those from marginalized groups, have told Jennings how they can relate to her story in ways they often don’t to popular media.

The fact that Native people are working as scientists, attorneys, lawmakers and other roles that serve their communities, Jennings said, is the film’s central message.

“That’s my biggest take-home: that we’re here, we’re making the work really meaningful and including our communities, and also using a variety of techniques that make the work better for everyone,” said Jennings, who is working to schedule an Arizona screening of the film. “Including Indigenous scientists and knowledges make science better for everyone.”

Showing Indigenous Communities ‘at the Decision-Making Table’

“Run to Be Visible” takes viewers along as Jennings plots her 50-mile run along passages 4, 5 and 6 of the Arizona Trail, near the border of Arizona’s Pima and Santa Cruz counties.

The film also highlights Jennings’ doctoral dissertation work, which examined how the Tohono O’odham Nation reclaimed a plot of its land that had been leased and mined for copper. The reclamation process, between 2009 and 2019, involved tribal leadership using traditional knowledge to select a seed mix of plant species native to the Sonoran Desert, which was then incorporated into a strategy to manage mine waste.

Jennings’ dissertation combined several of her research interests, including soil ecology, mining policy and Indigenous sovereignty, and allowed her to investigate why mines in Arizona are disproportionately located on or near tribal lands. The paper also examined the significance of directly involving Native communities in creating environmental solutions that better serve them – something Jennings found doesn’t happen enough.

“We can’t just be part of the conversation – we need to be at the decision-making table,” Jennings said, adding that there is sometimes a misconception that there aren’t many Indigenous people working in science.

“There’s actually a robust community of Native people who do science and who do policy and who do law, and I think it’s really important that we’re ensuring that we have these respectful and collaborative conversations with Native communities.”

Jennings’ commitment to learning more about the tribal consultation process went well beyond the field sampling and other research she was initially hired to do, said her doctoral adviser Julia Neilson, director of the UArizona Center for Environmentally Sustainable Mining.

“She’s done a really good job of understanding the needs of industrial society, but also understanding – because of her own culture – how tribal communities’ land has been abused, and how do we move forward constructively,” said Neilson, who appears in the film. “That’s where I feel like she’s got a unique insight, and I think she’s done an excellent job of using her Ph.D. to improve her expertise in both those areas.”

The People Who Believed

The day of Jennings’ run – which involved about 11 hours of total run time with two hours at aid stations – appears about two-thirds of the way into the film. A series of montages show Jennings at various stages of the run, with some miles labeled with their honorees.

Some names are familiar to the University of Arizona community: Jennings dedicated her first mile to Karletta Chief, a University Distinguished Outreach Professor of Environmental Science and a renowned Diné hydrologist, and mile 42 was dedicated to Ofelia Zepeda, a Regents Professor of Linguistics and a Tohono O’odham linguist and poet.

A complete list of honorees appears at the end of the film.

Jennings’ determination never appears to waver during the run. But she said she stayed focused, as exhaustion and overwhelming emotions set in, by thinking about the people who supported her on her journey to becoming “Dr. Jennings.”

“I am the product of the people who believed in me,” Jennings said. “As I was running, I was thinking about everyone from the pre-K teacher or the elementary teacher who gave me extra tutoring, to my language teachers, to my professor in undergrad at my community college telling me I should do research, and all the people along the way who believed in me.”

Celebrating Ingenuity and Relentlessness

Jennings was a runner before she was a scientist, but running, she said, led her to science. She first took up the sport as a middle schooler in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

“It was during my science classes that I started to have the language to describe what I was noticing in the landscapes (as I was running),” Jennings said. “Why are certain plants growing here and not here? Why is there a gulch forming here and not here? Why is this soil color different here from what it is here?”

An honor run was perhaps a natural choice to intertwine her two passions. The idea, Jennings said, came from a similar honor run by Jordan Marie Daniel during the 2019 Boston Marathon. Daniel dedicated the 26.2-mile race to 26 missing Indigenous women, saying a prayer for each during each mile.

Jennings, inspired by Daniel’s run, aimed to do something similar, but in a way that honored Indigenous peoples’ victories.

“I think often in media we hear Native people depicted in this deficit model, from the perspective of traumas and poverty and disparity,” Jennings said. “I wanted to flip that narrative and celebrate our ingenuity, our relentlessness to thrive in these systems, particularly for Native students.”

Jennings reached out to Daniel to see if she would consider attending her run, and to Jennings’ surprise, Daniel said she was starting a film company and asked if she could make a documentary about the run.

Jennings, who had just begun working with Patagonia as a brand ambassador, pitched the film idea to the company, which agreed to help finance the project. The film was also supported by Rising Hearts, an Indigenous-led organization that elevates Indigenous voices toward improving racial, social, climate and economic justice.

Daniel co-directed the film with Devin Whetstone, a California-based cinematographer. Jennings is the film’s story editor.

“For me, wanting to work in academia, I think it was really important to not just be the subject of the film, but to also demonstrate the research I conducted, and the capacity of science communication using film, which is why I am delighted to have earned a story editor credit,” Jennings said.

Promoting the Presence of Indigenous Scientists

As a postdoctoral researcher, Jennings’ work in the College of Public Health builds on the research she did for her dissertation. She’s working with UArizona’s Native Nations Institute to develop a framework to help researchers more effectively consult with tribal nations.

“In my dissertation work, I outlined that this process that’s used to engage and consult with tribal nations has been recognized as insufficient, both from tribal nations and from the mining industry,” Jennings said, adding that she aims to help create “a really useful piece of framework as more people are wanting to engage with tribal nations while trying to figure out how you do so in a community-centered process.”

More specifically, Jennings’ research focuses on data and data sovereignty – the idea that a sovereign nation has the right to govern the collection, ownership and application of its own data. Her postdoctoral mentor, Stephanie Carroll, an assistant professor of public health and associate director of the Native Nations Institute, also leads the Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance, a UArizona lab that develops research and policy solutions that enhance data sovereignty.

“Run to Be Visible” is a good example of how Indigenous people can highlight their presence in fields where they are underrepresented, such as science, said Carroll, who also appears in the film.

“Instead of fighting invisibility, we’re promoting our presence, which is incredibly important because it not only provides the vision for somebody else that others are there, but it allows connection,” said Carroll, who is Ahtna, a citizen of the Native village of Kluti-Kaah, an Indigenous community in Alaska.

She said she hopes that connection helps inspire up-and-coming Indigenous scientists to take up and continue the kind of work Jennings and others are doing.

Refusing to Leave the Future Hanging

Jennings’ commitment to Indigenous scholars of the future may be best illustrated by a scene that didn’t make the film’s final cut.

As Jennings trudged across the finish line in the dark on March 20, somewhere along a stretch of rural road near Colossal Cave, her coaching team, her family and friends, and the film’s crew cheered and embraced her.

Then, she looked at her distance-tracking watch.

The route she and her team had mapped was about half a mile shy of 50. Exhausted and emotional after 11 hours of running, Jennings just wanted to be done.

But then she remembered who mile 50 was dedicated to.

“That mile is dedicated to the Indigenous scientists of the future,” she said. “I was like, ‘OK, I can’t leave the future hanging.'”

Jennings and her team of family, friends and filmmakers ran the final half-mile together.